Success Factor Gender Diversity: Measures and Inhibiting Factors

Recommendations for the establishment of best-qualified women in top Swiss management boards

Written by Dr. Fabienne E. Meier, Partner, Knight Gianella, April 2022.

Most female and male board members prioritized a clear and consistent stance by the CEO to anchor gender diversity in Switzerland in the longer term, placing the reconciliation of family and leadership positions in second place. So, it takes more than the new gender benchmark. It takes a real conviction that gender-mixed leadership teams are more successful.

The inhibiting factors should be better addressed. Paying the price of a career (i.e., also making personally drastic compromises for a career) is seen as a particularly high inhibiting factor. Other important reasons are a weaker presence in business networks, lack of role models, lack of time availability, and lower international mobility of women.

Basis for the recommendations

The analysis and the recommendations derived from it are based on Knight Gianella’s BoD survey 2021/22, which was conducted online in Q3 of 2021 by Prof. Dr. Stefan Michel, Dean at IMD. The results can be considered representative given the very high response rate of over 29.8% of the 705 board members in listed and large unlisted Swiss companies and the constant ratio of women at 24%. Of the 210 participants, 75% hold a mandate in listed companies, 34% in family-dominated companies, and 18% in state-related companies. The majority serve on at least one audit committee (61.7%), compensation committee (59.6%), and nomination committee (54.6%).

Additionally, 180 one-on-one interviews with board members and CEOs from listed and large unlisted companies in Switzerland, as well as a comprehensive literature review, have been conducted in the period from September 2020 to November 2021.

Current situation in Switzerland

The establishment of gender diversity in Switzerland has arrived at the agenda of top management boards. The gender benchmark, which was introduced in January 2021 in the Swiss Stock Corporation Act, has proven to be a useful lever to drive the transformation in Switzerland and to bring best-qualified women into the top management (BoD, CEO, EM) faster. On average, 26% of the board of directors and 14% of the executive management of the companies surveyed are women. Current figures also show that 69% of the companies employ at least one woman on the executive board. At the same time, however, it must be noted that 31% of the companies still do not have a woman on the management board. Certain industries are affected more than others. For example, only 3 of 73 retail banks are in the operational hands of female CEOs. A comparable situation can be found in the MEM (mechanical, electrical, and metal) industry, which is looking for technically oriented or affine profiles. Here, female profiles accounted for less than 10% of students at the ETH until 2003 (and less than 20% at the HSG).

Also, companies in industries with a low percentage of women are confronted with the fact that there are not only few best-qualified women, but that they are strongly sought after and receive many job offers. If the dynamics in the team are not right, these women quickly migrate to other companies and industries where they find more suitable conditions. This raises the question whether companies will succeed not only in attracting the missing female profiles, but also in retaining them over the long term.

It is also interesting to note that most of the top management positions are held by women without any Swiss nationality (54%)—mainly women from the USA, Germany, England, France, and Italy—which gives a mixed picture of the current situation in Switzerland. Switzerland as a business location needs its own pipeline of best-qualified women, which companies must acquire themselves to remain competitive in the long term. In the Economist's Glass-Ceiling Index, Switzerland still ranks 26th out of 29 OECD countries. So, it takes more than the new gender benchmark. It takes genuine belief that gender-mixed leadership teams are more successful.

Measures for better gender diversity

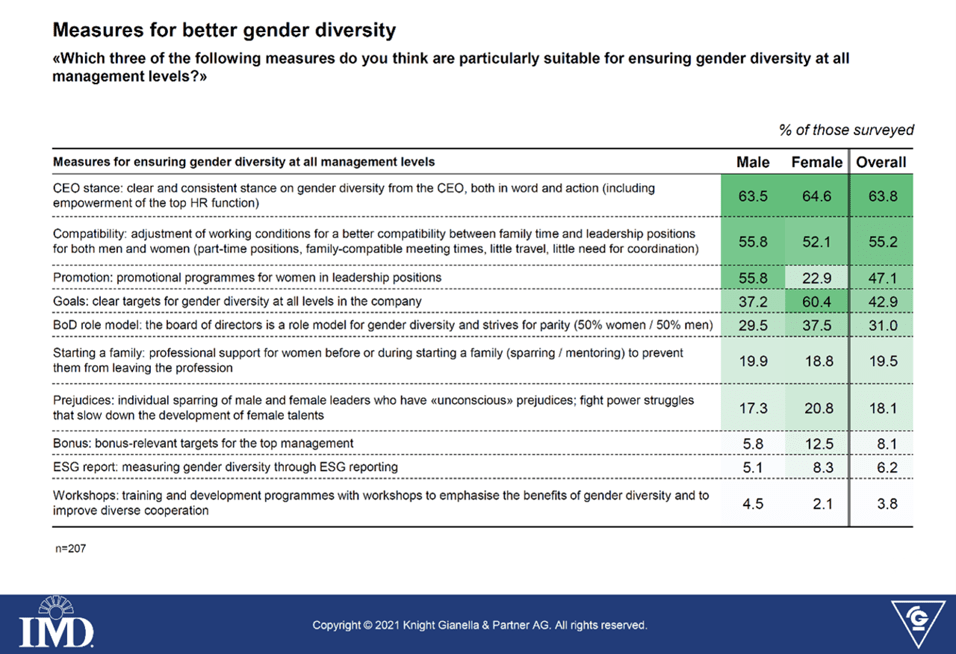

In Knight Gianella’s BoD survey 2021/22, female and male board members identified measures (see figure) to ensure gender diversity at all hierarchical levels of the company.

64% of respondents prioritize the clear and consistent stance of the CEO (in word and action), and 55% prioritize the compatibility of family and leadership positions. However, when it comes to certain inhibiting factors, female and male board members have a divergent view of the topic of gender diversity. While 35% of women think that societal values inhibit gender diversity and that the gameplay in business must change, this opinion is shared by only 4% of men. Accordingly, women favor the introduction of clear targets (including quotas), while men think that gender diversity can be solved through promotion programs.

First measure: stance of the CEO (in word and action)

CEOs are the most important identification figures for leaders in the company and carry the topic of gender diversity internally and externally with a clear and consistent stance. On the one hand, they represent the interests of the board of directors and are responsible for the operational management of the company. On the other hand, they can strengthen the CHRO and assign them competencies and budgets to proactively and convincingly anchor the topic of gender diversity in the company. If the CEO sets an example by addressing the issue of gender diversity, it will be easier for the organization to achieve its goals. This assumes that the shortage of women in the company can be met effectively.

CEOs and former CEOs (now on the board of directors), who encountered gender-mixed teams early in their professional careers, are currently committed to this in their own companies. They have come to appreciate the benefits. And they are aware that the dynamic of a gender-mixed team changes, has a positive effect on discussion and exchange, and consequently promotes innovation and competitiveness.

Second measure: compatibility of family and leadership positions

Today’s crunch point lies in the compatibility of family and leadership positions. Many leadership positions in Switzerland still allow little flexibility and are difficult to balance with family planning. At least until the problem is solved from a social perspective (incl. all-day care), families rely on expensive childcare and other costly accompanying measures to master the complicated Swiss school system. Further complicating the situation is the fact that most companies in Switzerland today are internationally active, and thus many leadership positions require international mobility. There needs to be a societal and economic shift in thinking so that more women are willing to pay the price of a career (i.e., also make personally drastic compromises in favor of a career) and later become available for top management positions. To better address this, the inhibiting factors for female careers (see inhibiting factors) should be understood. At the same time, mothers, or families with children, need to establish their own accompanying measures (childcare, household, and external services) in a more targeted manner, or make use of them, as is already the case in many neighboring countries.

At this point, it should be mentioned that men of the new Gen Z will also support their wives/partners more strongly in the future. Several studies show that the compatibility of family and leadership positions is also increasingly becoming a key criterion for younger men when choosing an employer. Thus, the issue is important for both genders and a competitive advantage for companies in attracting and retaining talent.

The dilemma: goals versus promotion – "unconscious bias" or support?

Board members have a divergent view of gender diversity when it comes to societal values of women in leadership and—consequently—their development towards the top management boards. While societal values play a role for women, they are more secondary for men. Men believe that gender diversity can be solved through promotion programs. Now, there is the question whether there is an "unconscious bias" between men and women. Although the bias is dismissed in the BoD survey, the evaluation shows clear differences in perception between the sexes. To solve the problem in the long term, we need both genders to come closer together and bridge the differences in perception. It takes the will of both genders to want to work together optimally and to benefit from the advantages of gender-mixed management teams.

At the same time, it should be noted that some women need more "profit and loss" responsibility and should be proactively encouraged in this area. A study by Advance and the University of St. Gallen shows that women have less experience in this area, especially because they have been promoted less in the family years between 31 and 50 as a "risk group"—with or without children. This is also one of the reasons why most men think that promotion programs for women are necessary.

Also, it should not be forgotten that a leadership position, in addition to technical competence and "profit and loss" responsibility, demands and will continue to demand a high level of commitment, availability to stakeholders, and the will to see things through. Too many changes without demonstrable performance success are usually counterproductive both for the own reputation and for the longer-term success of the company, especially if they take place outside the same company.

Inhibiting factors for better gender diversity

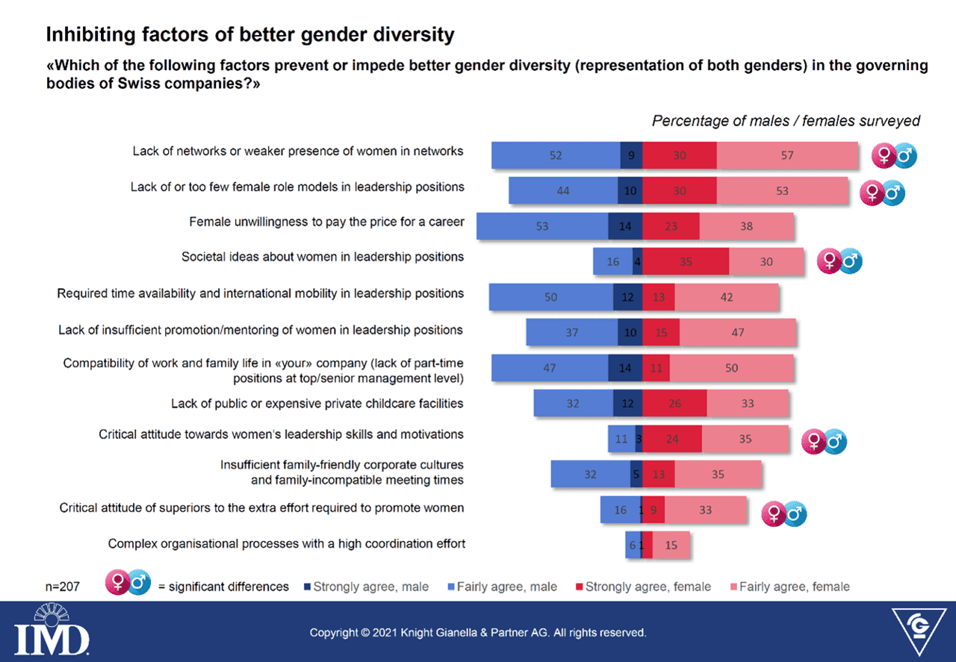

Knight Gianella’s BoD survey 2021/22 identified several inhibiting factors (see figure) as to why women in Switzerland often do not make it onto the boards of listed or large unlisted Swiss companies. Most women and men who participated in the BoD survey agree that paying the price of a career (i.e., also making personally drastic compromises in favor of a career) is a particularly high inhibiting factor. Other important reasons are a weaker presence in business networks, lack of role models, lack of time availability, and lower level of international mobility of women.

Why

are only few women willing to pay the price for a career

Our findings show that the problem of balancing family and work—with the high demands of a leadership position with international mobility, expensive childcare, and other costly accompanying measures to master the complicated Swiss school system—brings most women, or families, to their knees. Companies risk losing the 70% of women who have children. Consequently, the current career models should be adapted. In Switzerland, we need flexible part-time positions at a high level that involve little administration and little travel. Ideally, these part-time positions should include "profit and loss" responsibility. In this way, the years can be bridged when the children are small and the problem of childcare has not yet been solved from a social perspective. Once this phase is over, the women should return to professional life as soon as possible with a full-time workload. They will then be available later for a position in top management.

We also often encounter a corporate culture at the highest level in which there is the belief that you have to subordinate everything to a leadership position in a listed or large unlisted Swiss company. In addition to a heavy workload, an executive position also requires international mobility and a willingness to travel. Most women would rather not take on this burden, especially not during the time span in which they have to manage the balancing act between career and family.

Conclusion: A social and economic shift in thinking is needed for more women to be willing to pay the price of a career. There is a need for genuine conviction that gender-mixed management teams are more successful. It should be possible to work in different ways depending on the life phase, and career models should be flexibly adapted to these circumstances. However, it must not be forgotten that a leadership position at the executive level demands a high level of commitment and requires the demonstrable performance success of a competent top management board.